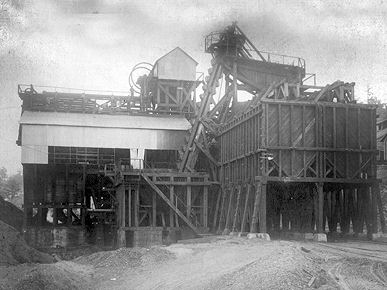

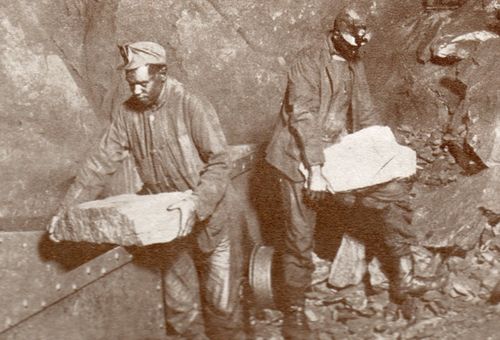

Birmingham, Alabama, founded in 1871, grew as an industrial center in North Alabama, focused around mining and the production of pig iron following the discovery of iron ore, coal, and limestone in the region. The city experienced an influx of industrialists and laborers moving to Birmingham and its surrounding areas for job opportunities in mines, furnaces, foundries, mills, etc. This growth happened quickly, but lagged behind the immense success of northern cities, notably Pittsburgh, which Birmingham often became compared to. Also like these northern industrial cities, labor strife and violence plagued operations. The Alabama mines and industrial sites faced added tensions of segregation and racial animosity in the postbellum period. Racial violence including lynchings coalesced with labor violence and created a highly tense and dangerous environment.

Initially, Birmingham industrialists, such as Henry DeBardeleben, Daniel Pratt, and James W. Sloss, foresaw the mining industry in North Alabama as being capable of avoiding unions all together. They kept “skilled” (white) and “unskilled” (Black) laborers segregated. By maintaining a strong anti-union stance and a focus on “social order,” they believed union activity would stay in the North. This quickly proved an impossible dream.

Lynchings and racial terror, however, were not new phenomena, especially in the South. The Equal Justice Initiative’s Racial Terror Lynchings map breaks down the location of over 4,000 lynchings in the United States between 1877 and 1950. During this period, unionization and labor strikes overtook mines throughout the country. Birmingham proved no exception to this trend. Spikes in union memberships and mine walkouts took place in the 1890s, 1908, and again in the early 1920s. Miners took a stand for fair pay, better working conditions, and shorter working hours. Mine owners and states officials, including extreme anti-union industrialist Braxton Bragg “B.B.” Comer, governor during the 1908 strike, responded with the militarization of industrial sites including armed guards and strikebreakers.

Through these periods of heightened tensions and violence, I wanted to identify any connections between motive, style, or number of lynchings happening in North Alabama. By looking through newspapers, I pinpointed various miner victims from the 1890s through 1921. In addition to identifying victims, I wanted to reinstate humanity to these forgotten people whose stories found in newspapers often lacked detail, names, or resolution. Some names varied in spelling between papers or the men were identified only as “unnamed negro.” While giving an identity to these unnamed victims today proves essentially impossible, work can still be done to present what story is known to the public sphere. By giving victims their humanity and any identity that can be tracked through newspapers, these men become more than a statistic of a victim of racial terror.

From my sample of eleven lynch victims, I found commonalities in method and race among other factors. These victims were mostly Black males, with the exception of a couple of white men, and worked in mines surrounding the Birmingham area. Multiple of the victims were abducted from local jails, many were attacked by what newspapers referred to as a mob, and all cases faded from newspaper coverage in the following weeks. Some cases had newspaper coverage of trials and attempts at getting to trial. The large majority of the murderers were not arrested or, if they were, there was no mention in newspapers. Methods of lynching involved shootings most prominently with hangings and dynamiting of homes also common. The most surprising commonality found by looking at these cases as a whole was the consistency of newspapers in acknowledging these murders as lynchings as well as labeling the perpetrators as a mob. Starting this project, I held the assumption that language used would be less critical of white lynchers during this period of racial unrest. One theory for why this proved false could possibly be public criticism of continued industrial violence and unrest.

I chose the ArcGIS StoryMaps platform to present my information because it allowed the incorporation of images and text within an interactive map. Specific locations of the sites of lynching could be pinpointed to show proximity to one another. One limitation, however, was the lack of specific locations given for most lynchings. In addition, when a neighborhood marker such as a local business is given, but reported using an unofficial name, locating that exact location remains difficult. In the case of the Gintown lynching of Sam Lynn, the newspapers refer to the altercation taking place outside of Leonard Scott’s store, but no “Scott’s Store” is listed in Birmingham city directories during the period. To solve this mystery, I contacted the local “Graysville Alabama Memories” group and found the location of the store from various group members who grew up in the area. While this memory may not be exact on the location, the collective memories of the group narrowed it down to a specific street after one member recalled living next to the store as a child. For other difficult locations, I utilized Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for locations such as the original Brighton Jail in 1908. By using a mixture of primary sources and community input, I worked to narrow now the sites of lynching as accurately as possible.

I developed my StoryMap to first tell the story of these victims, providing details of when, where, and how the lynchings took place. Following this is a short history of industry in Birmingham and the Jones Valley region that explains why the mining industry developed in North Alabama. The next section provides the context of mining unions, strikes, and violence that spread throughout the country, including the mines in the Jones Valley. By reading the stories of the miners lost to violent lynchings, this project aims to give these victims the humanity lost to them as well as place these instances into the larger conversation of the history of Birmingham, history of industry, and the history of labor.

North Alabama Lynchings: Violence & Terror in the Mining District 1890-1921

Consulted Books:

- W. David Lewis, Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994).

- Henry M. McKiven, Jr., Iron & Steel: Class, Race, and Community in Birmingham, Alabama, 1875-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

- William Warren Rogers, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flint, Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994).

- Philip Taft, Organizing Dixie: Alabama Workers in the Industrial Era (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981).