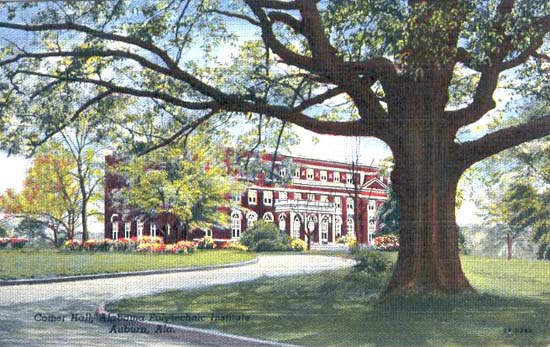

Being relatively new to Auburn and Auburn University, I did not know much about the campus other than the University owned a few plantation homes. Walking the campus during my first couple months here, I made connections to some of the names of buildings such as Comer Hall and the Graves Amphitheater. Other than being former Alabama governors, I knew B.B. Comer’s history of child labor at his Avondale Mills company and use of convict labor and of David Graves’s leadership within the KKK. Finding these names on buildings, especially that of Graves, proved an enormous surprise to me. Campuses throughout the country have buildings named for less than pure historical figures, but the experience of seeing it at my own university put into perspective the breadth of this issue. Through learning of names I didn’t recognize on buildings, I found that Auburn University should undertake a task to rename some of these buildings named for people who committed especially atrocious acts of inhumanity.

Aside from buildings, another marker of history I noticed was the Civil War cannon lathe next to Samford Hall. This massive piece of machinery placed out in the open and under the weather elements not only shows the University’s attachment to Civil War history, but that they don’t value this artifact. Having the lathe here itself isn’t a problem, but I think it should be stored somewhere inside, with proper signage to explain the machine’s use and why it came to Auburn University. Its location now is often overlooked and the machine will eventually rust beyond repair.

Overall, I truly believe that Auburn University has a history that should be expressed in place of names of prominent Alabama Confederates and white supremacists. Alumni and scholars who have gone on to complete great academic or humanitarian work could easily replace the names of Comer, Graves, and others on buildings. This symbolic act would create a more inclusive university experience as well as show that Auburn is a university willing to grow and adapt to change.