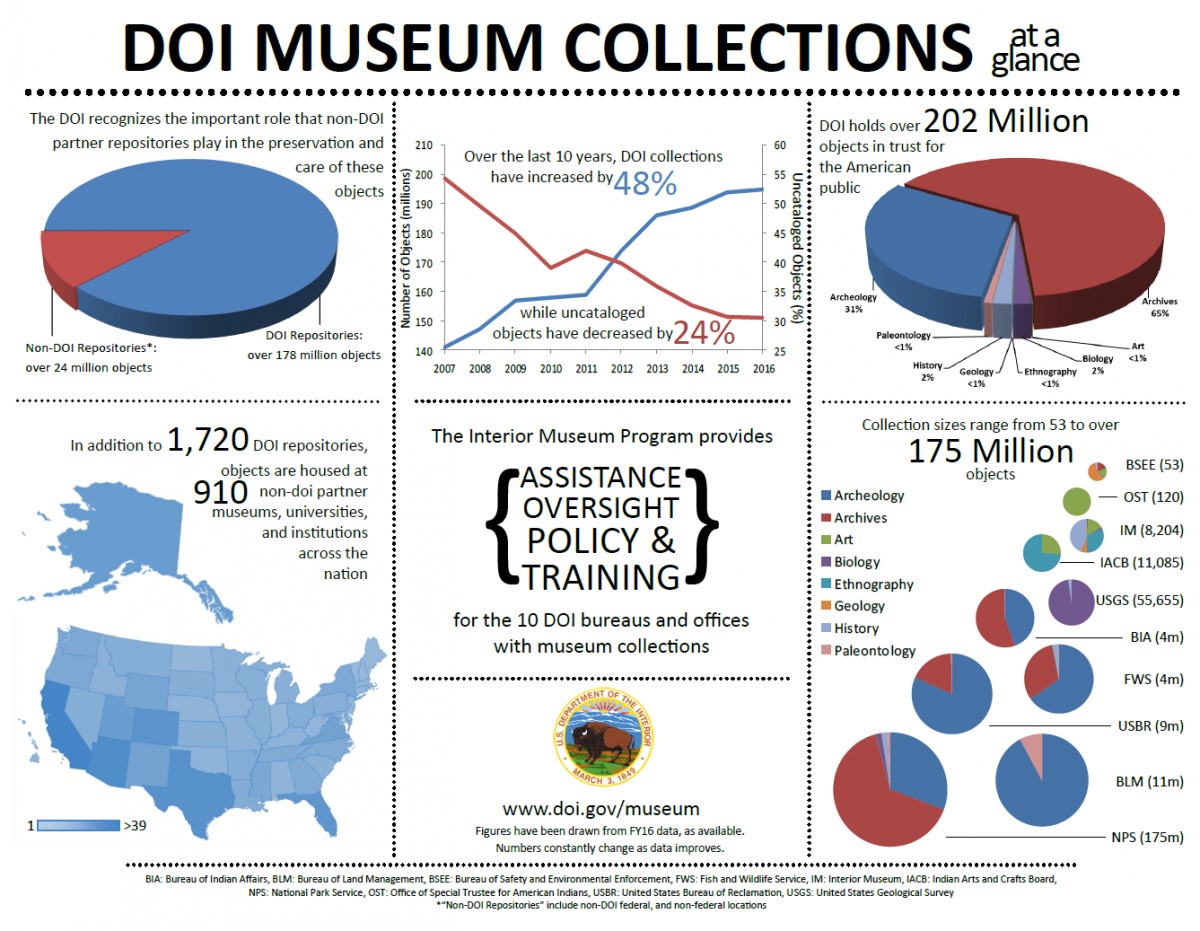

The infographic above is from the Department of Interior and details the incredible number of items that the department currently has in its various collections. While the Department oversees multiple federal agencies, the largest collection of items by a single agency is by far the National Park Service. On the front page of the National Park Service’s Museum Management Program, they boast, “The National Park Service is one of the world’s largest museum systems. There are 380 parks with collections that include over 45 million natural, historic, and prehistoric objects and 75,000 linear feet of archives. These collections tell powerful stories of the nation, its diverse cultures, flora and fauna, and significant events and innovative ideas that continue to inspire the world.”[1]

The archival work that both the National Park Service and the Department of the Interior are able to achieve is astounding and significant in the preservation of artifacts from all over of the United States. Yet when it comes to access, not all archives are created equal. While the National Park Service has utilized digital resources to offer online exhibits, digital catalogs, and educational resources for a select number of sites and artifacts, there is a larger number of archives that do not offer these digital means of access. This is where individual parks are challenged with the task of enhancing the means of access to their archives. The NPS Museum Handbook addresses the question of the “museum management responsibilities of the park” and includes “Promote access to cataloged collections for research and interpretive purposes through a variety of means, such as exhibits, interpretive programs, loans, publications, Web exhibits, and the Web Catalog.”

One park archive to consider how they may meet the responsibility of promoting access to the public is the archives at Horseshoe Bend National Military Park. One of the most basic ways to promote access of an archive is through addressing the public’s awareness, knowledge, and interest of simply what the archives are. While the National Park Service as a whole had the means to create a dynamic website that was aimed at highlighting promote specific artifacts, individual parks are often constricted to a smaller budget, staff, and resources. Individual parks still have access to social media. Rangers at Horseshoe Bend NMP could create social media post focused on the tasks that rangers do when they are in the role of curators and archivist. Similar to post focused on rangers work in the field, these post would help to promote public interest in the archives and even to educate some that may not know of what an archive is or that the park even maintains a collection of artifacts beyond the museum. Social media post could also focus on highlighting an artifact of the month in a reoccurring post that offers some images of an artifact, summary of the history of the artifacts, and what it takes to preserve that specific artifact.

Beyond utilizing social media to promote the education and awareness of the park’s archives, the park could also plan an on-site public program. A public program could mean offering a talk by the NPS Southeastern Regional archivist, or a park ranger in charge of the curatorial. Offering some insight into how the NPS approaches archives, how they preserve artifacts, catalog, accept donations, and how the park uses these artifacts. Not only would this allow for additional access to the archives, but it would offer education of what the archives are to the general public. Programs could also be less formal with ranger’s giving guided tours of the museum and providing visitors with insights into specific artifacts, similar artifacts in curation, how artifacts are selected for exhibits, and what it takes for the parks to preserve these artifacts.

[1] https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1454/index.htm